Not everybody can come into contact with the sap of this tree because it could easily result in swelling and an itching rash, particularly on the face. Such a phenomenon is popularly known as “lacquer corrosion”. This will last for several weeks. If, by a stroke of bad luck, someone is attacked by this “invisible” force of lacquer resin, the only way out is … to scratch. However, you will feel a bit of relief if you crumble fresh carambola leaves and rub them on the itchy skin.

Lacquer resin is noted for its difficult treatment and “caprices”: it will wrinkle, dry out and darken instantly when directly exposed to water, wind and sunlight. Lacquer growers can only obtain it between midnight and dawn. The sap thus collected is contained in large bamboo barrels covered tightly by sticking wax paper on their surfaces to make them air-proof. The containers of lacquer are afterwards taken away and left untouched for several months in a cool, dark, well-aired place until the different elements of lacquer settle into three major layers. Only then does the sorting out begin.

The uppermost layer is lacquer of the first stratum (reddish brown lacquer); it is least sticky, yellowish brown and limpid. The resin is then filtered to completely remove all impurities, put into earthenware or ceramic jars, and continuously and evenly stirred with bamboo or wooden sticks for several hours to get rid of vapour.

The next layer is lacquer of the second stratum; it is stickier and of darker, yellowish brown colour. Iron containers should now be used. One must stir the resin with an iron rod for several hours to obtain a black, glossy lacquer known as then lacquer. The undermost stratum is very sticky and soft, of muddy yellow colour. It stiffens when dried out and is called hom lacquer.

Asians have known about the techniques of using lacquer resin from very early times. The Chinese under the Shang dynasty (1384-1111 BC) used lacquer for decorating simple objects made of bamboo and wood because its durability enhanced the use value of these objects. Lacquer also served as an agglutinant in inlay and carving. During several feudal dynasties, lacquer met ornamental needs by highlighting motifs that decorated the palaces of kings, lords and noblemen, as well as other architectural elements, weapons, carriages, musical instruments, and containers and bottles. Hence over time the artistic functions of lacquer became more and more recognized. In Japan, although lacquer was used as early as the 4th century BC, it was confined to items of daily use such as crockery or utensils for making tea. Not until the 4th century AD did the Japanese, along with the Koreans, have contact with the lacquer trade of the Asian continent. They were exposed to the various techniques of inlay, engraving, pumicing and ornamental styles with the basic techniques of making pictures such as drawing on a plane, pumicing, polishing and embossing. Japanese lacquer reached the zenith of its development; its influence grew far beyond the country’s borders and spread to European countries.

In Vietnam, lacquer also had a long tradition. More than 2,000 years ago, during the period of the Dong Son culture, the Viets already knew how to process raw lacquer for making useful things. Many household and cult objects were decorated with pictures and then coated with lacquer. They were found in ancient tombs discovered here and there in northern Vietnam. As far back as the Ly dynasty (11th century) or even earlier, lacquer was widely used in the ornamentation of palaces, communal halls, temples, pagodas and shrines. The know-how related to this craft was always kept secret and handed down within the clan of artisans, from fathers to children. Outstanding master hands were awarded and received titles by the King. The growing need for specialization inevitably led to the founding of guilds. One such guild would excel in processing lacquer while others distinguished themselves in gilding or in making vermilion powder. They gathered, lived together, and produced lacquer ware in a special ward along a well-known street named after this craft. Today, in Hanoi and some neighbouring areas, many streets, quarters and villages remain, still preserving this traditional lacquer production. Objects made of bamboo, wood, fabric, earth or leather, once coated with lacquer for protection and embellishment, will be glossy, lasting and watertight. As proof, there are the lacquered objects discovered recently in the sunken boats belonging to the Nguyen Lords in southern Vietnam; they were found intact despite the fact that they had been immersed in salt water for more than 100 years. That is the reason why lacquer is very widely used for decoration in arts and crafts and industry.

Over the centuries, Vietnamese lacquer ware was distinguished by its originality and high quality when coming into contact with similar products in neighbouring countries — Japan, China, Korea and Burma. It was omnipresent in Vietnam — from the links in the planks of fishermen’s boats and peasant household basket ware and wickerwork, to sophisticated arts and crafts articles such as sumptuous gilded objects and mother-of-pearl inlay work in furniture. Yet the lacquer craft, reflecting people’s aesthetic needs in everyday life, was still restricted to the decoration of household items and cult objects, such as religious statues.

We could say that the founding of the Ecole Superieure des Beaux-Arts d’Indochine had given a strong impetus to the birth of a new form of painting encouraged by two French artists: Victor Tardieu (1870–1937) and his associate Joseph Inguimberty (1896–1917). The contact with European classical painting caused the Vietnamese fine arts to undergo radical changes. However, these changes – including the expression of three dimensions on a single plane and the visual depiction of reality – were accepted and incorporated into the traditional subject matter and techniques of the lacquer craft.

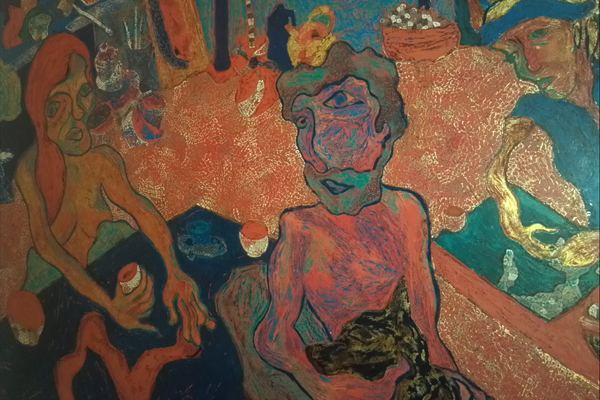

Impressed by the extraordinary tonalities and the latent resources of “black lacquer” in communal houses and pagodas, the two French artists urged their Vietnamese art students to explore this craft. Their encouragement awakened the latter’s national pride and this led to the birth of lacquer paintings, truly a major contribution to Vietnamese fine arts. Artists Tran Van Can, Pham Hau and Nguyen Gia Tri pioneered the development of the lacquer technique, from the simple decoration of architectural motifs in communal houses and temples or handicraft articles to the artistic drawings of modern lacquer pictures. They painted and did research passionately, mobilizing the traditional know-how of the lacquer craft while experimenting with new techniques. Their goal was to apply the laws of space and perspective concerning composition, shapes and figures (along with other painterly knowledge absorbed from the West) and at the same time to preserve the phantasmagoric character and other inherent features of lacquer art.

Basically, lacquer paintings incorporate the traditional colours — brown, black, red, yellow, white — and the technique of inlaying egg, crab and snail shells. Innovations include techniques in mixing dyes, the addition of various tones of green to enrich the colour scheme, the drawing of shapes and figures, the use of shade and light with a wide range of different tones, and methods of applying pumice and polishing. Realistic themes depicted in so many works through each historical period convincingly confirm the expressive, inexhaustible resources of lacquer art.

Another generation of artists, such as Nguyen Sang, Nguyen Tu Nghiem, Le Quoc Loc, and Sy Ngoc, has put its stamp on the value of Vietnamese lacquer art. Since 1934, international exhibitions have highlighted the achievements of lacquer art as a major landmark in the fine arts of Vietnam.